The European Union’s Radio Equipment Directive (Directive 2014/53/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on the harmonisation of the laws of the Member States relating to the making available on the market of radio equipment and repealing Directive 1999/5/EC) underwent a transformative evolution on August 1, 2025, marking one of the most significant shifts in product compliance within the European single market. What began as a straightforward modernisation of radio equipment regulations has evolved into a comprehensive cybersecurity framework that fundamentally alters how manufacturers approach device security, often with unintended consequences that have sent ripples throughout the global technology industry.

The Pre-August 2025 Era

Prior to August 2025, the RED operated under a framework that had evolved significantly since the directive’s introduction in 2016. While the directive replaced the older R&TTE Directive 1999/5/EC and maintained its core philosophy, ensuring radio equipment met basic safety requirements, electromagnetic compatibility standards, and efficient spectrum usage — the regulatory landscape was far from static. The critical transformation came through Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/30, adopted on 29 October 2021, which activated the dormant cybersecurity provisions of Articles 3(3)(d), (e), and (f) of the RED. This delegated act specified which categories of radio equipment would need to comply with requirements for network protection, personal data safeguards, and fraud prevention.

The implementation timeline itself tells a story of regulatory complexity. Originally scheduled for 1 August 2024, the cybersecurity requirements were postponed by Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2444 to allow the European standardisation organisations additional time to develop the EN 18031 series standards. This extension, requested by CEN-CENELEC due to the unprecedented technical challenges of creating harmonised cybersecurity standards for radio equipment, pushed the enforcement date to 1 August 2025.

During this transitional period, manufacturers could still achieve compliance through established procedures, testing their products against traditional harmonised standards and affixing the CE mark without addressing the comprehensive cybersecurity obligations that would soon transform the market. This approach had served adequately for conventional radio devices but was increasingly recognized as insufficient for internet-connected equipment that had evolved into sophisticated computing platforms vulnerable to cyber threats.

The EN 18031 Standards: Technical Framework for Cybersecurity Compliance

The introduction of the EN 18031 series represents the technical backbone of the RED’s cybersecurity transformation, developed by Special Working Group RED Standardization (CEN/CLC/JTC 13/WG 8) as a direct response to Articles 3(3)(d), (e), and (f) of the directive. These standards translate abstract legal requirements into concrete technical specifications, creating a comprehensive cybersecurity framework that addresses network protection, data privacy, and fraud prevention across the spectrum of internet-connected radio equipment.

EN 18031-1:2024 establishes fundamental security requirements for internet-connected radio equipment, introducing (at least) seven core security mechanisms that form the foundation of device protection. These mechanisms include access control (ACM) for protecting sensitive device functions; authentication (AUM) for verifying user identities; a secure update (SUM) for maintaining device integrity throughout its lifecycle; secure storage (SSM) for protecting critical data; secure communication (SCM) for safeguarding network traffic; network monitoring (NMM) for detecting anomalous behaviour; and resilience (RLM) for maintaining functionality under attack. The standard employs a “technology-agnostic” approach, focusing on security outcomes rather than prescribing specific implementation methods, allowing manufacturers flexibility while ensuring comprehensive protection.

EN 18031-2:2024 extends these requirements to equipment processing personal data, including children’s products, toys, and wearable devices. This extension recognizes the particular vulnerabilities associated with personal information processing and introduces additional mechanisms such as Deletion (DLM) for secure data removal, Logging (LGM) for security event tracking, and User Notification (UNM) for informing users of security issues. Meanwhile, EN 18031-3:2024 addresses equipment handling financial transactions, implementing specialized protections against fraud and unauthorized activities.

EN 18031 Standards Overview

| Standard | RED Requirement | Scope | Key Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| EN 18031-1 | RED, Art. 3(3)(d) | Common security requirements for general internet-connected radio equipment |

|

| EN 18031-2 | RED 3(3)(e) | Radio equipment processing personal, traffic, or location data |

|

| EN 18031-3 | RED, Art. 3(3)(f) | Internet-connected equipment processing virtual money or monetary value |

|

Important Compliance Notes:

- Multiple requirements may apply simultaneously to a single product

- RED 3(3)(d) applies to ALL internet-connected radio equipment

- RED 3(3)(e) applies even to non-internet connected devices if they are childcare products, toys, or wearables that process personal data

- Compliance with all applicable requirements is mandatory for CE marking

The assessment methodology underlying EN 18031 employs a three-tier evaluation process that ensures comprehensive security validation. Conceptual assessment examines documentation and security philosophy through systematic decision trees, functional completeness assessment verifies proper implementation through practical testing, and functional sufficiency assessment evaluates effectiveness through advanced techniques including penetration testing, fuzzing, and code analysis. This rigorous approach ensures that compliance represents genuine security improvement rather than mere checkbox compliance.

Harmonised in Principle, Restricted in Practice

The practical implementation of RED requirements had revealed significant enforcement inconsistencies across EU member states, having created competitive disadvantages and market fragmentation. Different national authorities interpreted requirements with varying degrees of strictness, leading to “forum shopping“, where manufacturers chose entry points based on enforcement likelihood rather than technical merit. Germany’s potential fines reaching 4% of global annual turnover contrasted sharply with other member states’ more modest penalty structures, having created uneven competitive landscapes.

These enforcement disparities were compounded by varying capabilities among national market surveillance authorities and Notified Bodies. Some countries possess sophisticated cybersecurity testing capabilities, while others relied on basic compliance checking, resulting in different quality levels of security assessment across the single market. This variation undermined the directive’s goal of harmonized protection and created opportunities for non-compliant products to enter circulation through less stringent oversight jurisdictions.

The harmonization through EN 18031 technical rules actually expanded opportunities for self-declaration, though with important limitations. While no self-declaration was previously possible for cybersecurity requirements, manufacturers can now avoid Notified Body involvement if their products fully comply with EN 18031 without relying on restricted clauses. However, products that allow users to bypass password requirements, lack parental controls for children’s devices, or handle financial transactions without robust security measures still require Notified Body certification, creating a two-tier compliance system that disproportionately affects cost-sensitive manufacturers and innovative products.

Self-declaration under the RED is rooted in the Directive’s internal production control (Annex II). That means that a manufacturer can declare compliance on its own if it fully applies harmonised standards for the relevant essential requirements, including the new Article 3(3)(d)-(f) obligations addressed by EN 18031. In practice, however, self-declaration becomes fragile/gray-zone wherever software loading and software control are unrestricted: if a device permits installation or execution of third party or otherwise non assessed firmware, the manufacturer struggles to sustain the presumption of conformity purely via self-declaration (Annex II) and is typically pushed toward Notified Body involvement. In other words, the theoretical pathway for self declaration exists, but it narrows each time the product supports open software loading that materially changes the assessed risk profile and the assumptions underpinning compliance. Once a device permits non assessed third party firmware, the manufacturer can no longer rely on presumption of conformity via self-declaration.

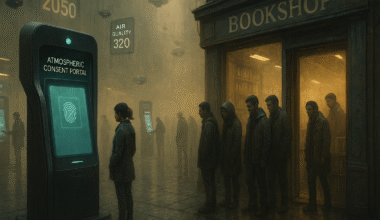

And here is the knot in the stomach: imagine a passionate technician or an Indie entrepreneur who wants to sell custom-built desktops, launch a new router and/or access point with OpenWRT, ship a custom Raspberry Pi board, or even introduce a smartphone “bare-metal”, with no preinstalled OS, to encourage GrapheneOS or LineageOS. These ideas often found in local business plans or target a very narrow audience, but that’s exactly where new ideas really take off. However, because the product allows software installation beyond the initially assessed device software combination, self-declaration is no longer legally safe. This leads to costly third party involvement, with budgets in the range of € 50.000 – € 150.000 for certification — numbers that are disproportionate for an Indie player and discouraging for experimentation & innovation. The paradox is that a framework designed to promote resilience ends up taxing openness and penalizing the MVP (Minimum Viable Product) and/or Agile mindsets — the creative DNA that keeps the open-architecture hardware and open-source software ecosystem vibrant.

Compliance Decision Flowchart

| Step | Decision Point | Possible Answers | Resulting Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Is your product a radio equipment? | YES → Continue to B NO → Not applicable |

Determines if RED applies at all |

| B | Is it connected to Internet? | YES → Continue to C & D NO → Check C |

If YES: RED 3(3)(d) applies |

| C | Is it a childcare product, a toy* or a wearable? *Falls under Toy Safety Directive 2009/48/EC |

YES → Continue to D NO → Check D |

Special category requiring additional scrutiny |

| D | Is it capable of processing personal, traffic or location data? | YES → Apply requirement NO → Check E |

If YES (and B=YES or C=YES): RED 3(3)(e) applies |

| E | Enables to hold, use or transfer money, virtual currency or similar? | YES → Apply requirement NO → Check other requirements |

If YES (and B=YES): RED 3(3)(f) applies |

One Union, Many Playbooks

The RED cybersecurity requirements create significant tension with other EU policy objectives, most notably the Right to Repair initiative and the Digital Markets Act. The Right to Repair framework explicitly encourages device longevity, user modification capabilities, and independent repair services—objectives that directly conflict with the security-through-restriction approach adopted by manufacturers in response to RED requirements. When devices become locked down to ensure cybersecurity compliance, users lose the ability to extend device lifecycles through custom software, contradicting environmental sustainability goals.

The Digital Markets Act further complicates this landscape by promoting platform openness, alternative app stores, and reduced gatekeeper power. Yet RED’s implementation has encouraged manufacturers to create more closed systems with restricted modification capabilities, potentially strengthening the very platform lock-in that DMA seeks to address. This regulatory contradiction places manufacturers in an impossible position: opening systems to comply with DMA while simultaneously locking them down for RED compliance.

The environmental implications are particularly concerning, as locked bootloaders and restricted modification capabilities reduce device longevity and increase electronic waste. Users who previously could extend device life through custom firmware installations now face forced obsolescence when manufacturers end support. This outcome directly contradicts the EU’s circular economy objectives and sustainable development goals, creating a fundamental policy inconsistency that requires urgent resolution.

The Android Bootloader Controversy: A Troubling Precedent for Digital Freedom

The most concerning consequence of the RED cybersecurity requirements emerged through manufacturer responses that appear to exploit regulatory ambiguity for commercial advantage. Samsung’s decision to disable bootloader unlocking in One UI 8, implemented mere days before the August 1 deadline, represents a disturbing erosion of user control that threatens decades of innovation from the open source community, with reports indicating the OEM Unlock path has been removed entirely and the bootloader no longer contains the code needed to unlock at all. This restriction eliminates access to custom firmware solutions that have consistently extended device lifecycles well beyond official support, with projects like LineageOS routinely keeping devices secure and usable for years after vendors stop updates. Compounding the concern, Samsung simultaneously announced third party evaluation of its 2024–2025 TVs, monitors, digital signage, and e paper displays by TÜV SÜD for compliance with RED’s upcoming cybersecurity rules. Samsung framed this as a “marker of global trust” and a key part of its strategy to be ready for regulation, showing that the company is committed to being as aligned with RED as possible and to show that alignment across all of its product lines. The juxtaposition — locking down phones while celebrating RED certification momentum for displays — underscores how a risk averse reading of Articles 3(3)(d)–(f) and the delegated act can be leveraged both to tighten control over software on mobile devices and to market early compliance wins elsewhere, reinforcing a narrative that strict lock down is the safest (and most PR friendly) path under the new regime.

A fair & calm reading of the legal framework leaves room for legitimate disagreement on how far vendors must go to restrict software, even if recent choices look more like policy preference than hard legal compulsion. Articles 3(3)(d)-(f) of the RED target network integrity, data protection, and fraud prevention rather than prescribing “authorized” or “signed” firmware per se, but in practice those broad objectives, the delegated act, and the pressure to pass conformity assessments all make it very likely that execution paths will be tightly locked, especially when software sideloading makes it harder to assume conformity and pushes manufacturers toward a Notified Body. Recital 19 does warn against abusing software verification to block independent software, but its wording is vague and abstract and can be overshadowed by the subjective judgments of technocrats or lawyers during risk assessments, liability analyses, and uneven market surveillance — so its protective effect may be underweighted in early compliance strategies. Against that backdrop, it remains technically and procedurally plausible to reconcile device security with user and consumer interests: the EN 18031 standards require cryptographic verification and secure update mechanisms, objectives readily achievable through user enrollable signing keys or dual key systems that maintain security while preserving user control, as demonstrated by UEFI Secure Boot implementations on personal computers (including Linux).

Verification by radio equipment of the compliance of its combination with software should not be abused in order to prevent its use with software provided by independent parties. The availability to public authorities, manufacturers and users of information on the compliance of intended combinations of radio equipment and software should contribute to facilitate competition. In order to achieve those objectives, the power to adopt acts in accordance with Article 290 TFEU should be delegated to the Commission in respect of the specification of categories or classes of radio equipment for which manufacturers have to provide information on the compliance of intended combinations of radio equipment and software with the essential requirements set out in this Directive.

What makes this interpretation particularly troubling is the stark contrast with other manufacturers’ responses. Google continues supporting bootloader unlocking on Pixel devices, Fairphone maintains official unlocking documentation, and router manufacturers address RED requirements without eliminating custom firmware capabilities. This fragmented response suggests Samsung chose the most restrictive interpretation possible, sacrificing the vibrant ecosystem that has produced superior implementations. The decision appears less about regulatory compliance than about leveraging legal uncertainty to strengthen platform control.

Chaos & Regulatory Failure

The implementation chaos surrounding RED’s cybersecurity requirements exposed fundamental weaknesses in the European Union’s ability to manage its expanding regulatory framework. Within hours of the August 1 enforcement date, technology forums erupted with contradictory information, AI-generated misinformation claiming the EU had “banned Android customization,” and panicked discussions across Reddit’s r/Android or r/PocoPhones communities.

It is, in fact, fortunate that principled voices have consistently defended openness and user freedom against the risk of a de facto “radio lockdown.” NGOs have warned that software-loading controls, if implemented without safeguards, could entrench gatekeeping, marginalise independent firmware, and undermine repairability and sustainability — concerns that remain highly relevant as RED cybersecurity enforcement begins to bite. Their argument isn’t against security; it’s for security architectures that let users keep control over their data; like cryptographic verification, secure updates, and accountable risk management, without getting stuck with a vendor or stopping legitimate third-party software development.

This digital pandemonium reveals a deeper pattern of regulatory disconnect: a framework drafted at arm’s length from day to day engineering realities, interpreted through divergent corporate risk postures, and received by a public that increasingly views EU tech rules as heavy handed. Within days, “debunking” pieces emerged that rightly condemned AI generated misinformation but still missed key compliance mechanics, notably the conditions for self declaration under EN 18031 and when Notified Body involvement is actually required — subtleties central to market behavior and user rights. In a better regulatory culture, you wouldn’t notice the legislator at all: as Sir Stanley Rous (FIFA ex-president) said, one of the tests of a good referee is that you never hear about him. The rules should let the game flow instead of dominating it. But here, Articles 3(3)(d)–(f), the delegated act, and the restricted harmonisation notices were all unclear, which made it possible for different teams to read the playbook in different ways. While Samsung seized the moment to get rid of open bootloaders, there was little visible reaction from Google, Apple, or even Fairphone; the latter having user modification rights embedded in its very DNA. The same text produced conflicting outcomes, more suggestive of a gap between Brussels’ intent and market actually did or will do, rather than a clear legal obligation. If the EU wants to be the good referee, it must publish operationally precise guidance where harmonized presumption applies, where it breaks, and how open software loading can coexist with network integrity—so that security is elevated without turning compliance into a mechanism of vendor lock in.

The episode crystallizes growing public skepticism toward Brussels’ legislative machinery. When a directive ostensibly about radio equipment security transforms into restrictions on software that has kept millions of devices secure and functional for years beyond manufacturer abandonment, citizens reasonably question regulatory competence. The contradiction between RED’s apparent effects and simultaneous EU initiatives for Right to Repair, Digital Markets Act openness requirements, and circular economy goals suggests a bureaucracy generating conflicting mandates faster than it can reconcile them. This regulatory incoherence, where security justifications override established environmental and consumer protection principles, validates concerns that the European Union increasingly struggles to maintain consistency across its proliferating legislative initiatives.

The Path Forward: Balancing Security with Innovation

RED’s cybersecurity turn confronts a real and urgent problem: the mass compromise of low-cost connected devices that quietly became part of botnets and fraud ecosystems at a continental scale, as seen with waves of cheap Android TV boxes preloaded with malware, affecting well over a million devices globally and weaponizing home networks for click fraud and credential abuse. Against that backdrop, the EU’s choice to harden baseline security through Articles 3(3)(d)–(f) and the delegated act is defensible, and the EN 18031 series offers a pragmatic, testable way to operationalize network protection, data safeguards, and anti fraud mechanisms without prescribing specific implementations.

Yet the same framework has leaned too far toward restrictive interpretations that sideline open computing models, diminish user agency, and collide with parallel policy goals—from Right to Repair and open hardware practices to the DMA’s push for platform openness and reduced gatekeeper power. A healthier trajectory demands precise guidance on when self declaration truly applies under EN 18031, how open software loading can coexist with secure boot and update integrity, and where RED’s cybersecurity aims must be reconciled with pro competition and sustainability mandates rather than overriding them by default. For readers tracking these tensions across EU digital policy, prior analyses on GDPR overreach, the enduring problem of cookie‑consent theater, and a Greek‑language deep dive on GDPR’s practical pitfalls offer telling precedents of well‑intentioned regulation drifting into complexity that empowers intermediaries while burdening smaller innovators — patterns Europe should avoid repeating as RED and the upcoming EU Cyber Resilience Act mature.